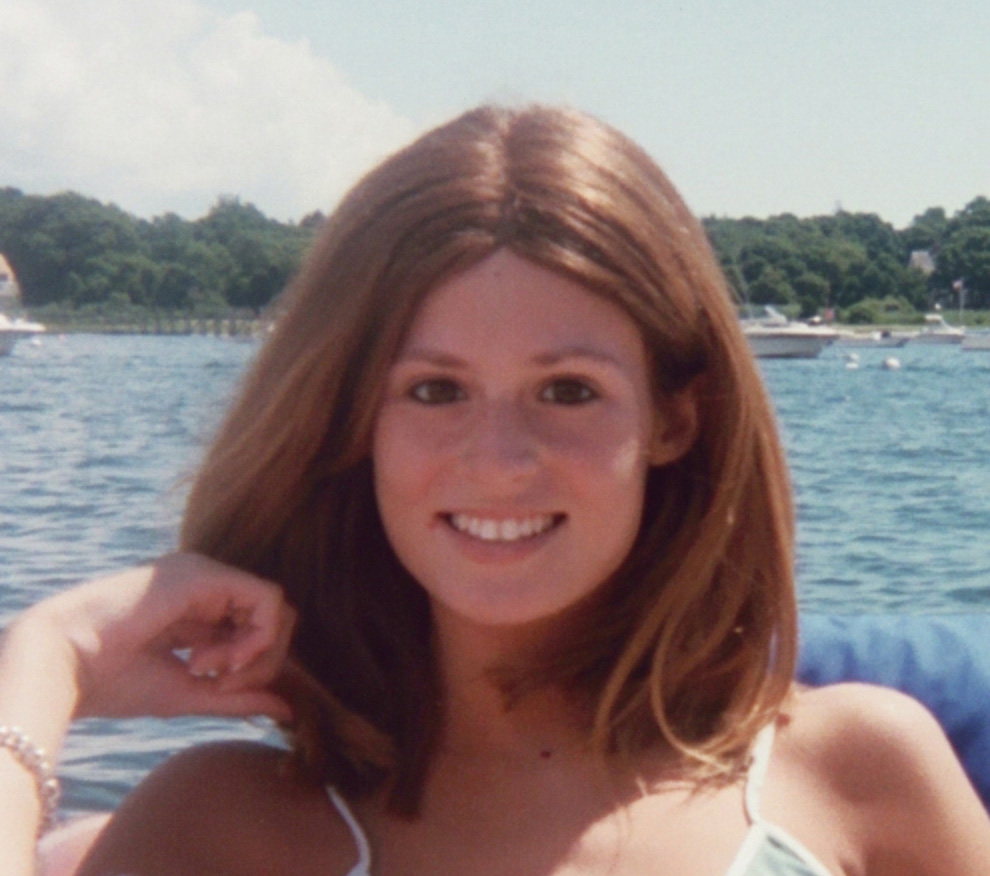

A Q&A with Diane Atwood, Founder of Catching Health, and the Conversations about Aging Podcast

Val Walker

Diane Atwood was a health reporter at WCSH-TV for more than twenty years, and later a marketing and public relations manager for Mercy Hospital in Portland, Maine. She is now a full-time blogger and podcaster on health issues, specializing on aging and isolation. Diane Atwood is the founder of Catching Health, and the podcast, Conversations about Aging. She describes her mission as “Health reporting that makes a difference.”

Introduction

Diane Atwood is a master interviewer, profiler, and journalist, well-known in Maine for her deep and richly detailed conversations with her interviewees on her blog and podcasts. I was honored that she recently interviewed me about the release of my new book, 400 Friends and No One to Call.

Indeed, it was Diane’s interview with me that inspired me to interview her. She was, quite frankly, a wise and seasoned interviewer who could teach me and others about her craft. I have always found profiling and interviewing people to be a fine art—particularly if we could capture the essence of that individual through their stories revealed through thoughtful and leisurely paced conversations. I have a story to tell about how Diane interviewed me, as it sheds light on how she works her magic in these times of rushed and fragmented conversations in our digital age.

On March 18th, the day of my interview, everyone in the Northeastern US was scrambling to prepare for their COVID-19 lock down. I was in the throes of adjusting to (and grieving) the drastic loss of dozens of speaking engagements, book signings and classes—indeed, the loss of my business-- and a terrible time to release a new book! I hardly wanted to be interviewed at all, as I still had not had time to wrap my mind around how COVID-19 had radically changed the meaning of my book, if not the magnitude of my book’s message about loneliness and isolation. I didn’t feel prepared to speak confidently about breaking out of isolation because I was clueless about how I would pay my rent next month. How dare I speak as an expert on social isolation and loneliness when I felt cut off from my clients, networks, colleagues, and friends who were all as isolated as I was?

But within minutes of our phone call, Diane put me at ease, welcoming my book into the world, inviting me to tell my story--the good, the bad, and the lonely--about why I wrote my book and what my message meant during these pandemic times. Her steady and friendly approach, gently probing, permitted me to trust her judgment and guidance as we delved into profound storytelling. Diane’s deep exploration helped me grasp a new perspective of my book’s message in times of social distancing, giving me a clear vision of how my book was going to help people survive isolating times. Her Q&A with me etched out the ways my life’s work was meaningful and vital at this time, and I am deeply grateful for her gift as an interviewer, profiler and storyteller. Her interview with me left me with a beautifully unique portrait of my essence and my life’s purpose, not just a description of my book.

With this first-hand experience of being her interviewee, I can attest to how Diane shares her gift with older seniors who are eager to have their life story told and their vibrant essence celebrated and shared. Her podcast series, Conversations about Aging, reflects her passion and dedication.

A Q&A with Diane Atwood

Val: What got you interested in doing interviews with seniors in their homes?

Diane: A couple of years ago, I went to a conference about the isolation and loneliness of seniors in rural Maine to report on this topic. I already knew that loneliness was deeply entrenched in rural society. After attending the conference, alarmed about seniors living alone in the empty, sparsely populated landscapes of Maine, I felt a call to visit seniors in their homes--just to engage them in conversation, storytelling and reminiscing. Perhaps I could help them feel less lonely this way. It was clear seniors needed meaningful and personalized conversation, and they longed to share their life experiences with others. I decided to start a podcast where I could post interviews with people over age sixty, calling it Conversations about Aging. And further, having deep, long conversations for up to two hours might be particularly rewarding—mutually speaking.

Diane with interviewee, Wayne Newell

Val: What do you especially enjoy about interviewing seniors and creating podcasts of their stories?

Diane: I love it when I ask someone, ‘Tell me about your life,’ and suddenly our conversation takes on a life of its own! Our conversations are adventures, and, as the one asking the questions, I have the power to steer the adventure, like a guide through their exploration of their life. My passion for interviewing people is to help them find meaning in their stories. This is how I feel I am making a difference. I believe people are starving to share, on a personal level, what matters about their lives. I love to see their eyes light up, and then our conversation deepens, bringing their past up to the present.

After I have arrived at their home and settled into asking questions, I have often heard them remark, ‘Nobody’s ever asked me these kinds of questions before.’ They usually are surprised at first. But they appreciate my interest in them, and they seem to like that I’m not afraid to ask them personal questions that typically didn’t fit daily chatter.

Val: What kinds of questions do you ask?

Diane: One of my favorite things to ask is, ‘What makes it a good day for you?’ I’ve heard answers such as, ‘What makes a good day for me is just to hear the birds.’ Or, ‘That I have someone to show my pictures to.’ Or, ‘That I have another day to look forward to.’

And so many are grateful to see me, and tell me, ‘Thank you for travelling so far to hear my story.’

Another question I ask is, ‘Do you feel lonely?’ It’s astounding the range of answers I get. I have found that isolation is not always the cause of loneliness. You can have lots of people around and plenty to do but still feel isolated. Or you can live days and weeks completely alone and enjoy your own company alongside the comfort of nature and animals.

One woman in her 90s who lives alone in rural Maine remarked, ‘I enjoy my own company surrounded by beautiful memories.’ She loves her quiet life of solitude.

On the other hand, I spoke with a man in an assisted living community who had plenty to do every day, but still felt lonely. His one, painful reason for being lonely was that he could not interact with his kids as often as he’d like.

I believe loneliness has more to do with a lack of meaningful connection in our lives.

Val: Yes, I so agree that meaningful connections are essential as we age. What do you believe fosters meaningful connections?

Diane: First of all, just look at all the losses in their lives. Loss of friends, family, work—and all the ways we have maintained structure throughout our lives, especially through rituals and routines—these have disappeared. They have lost their patterns of behavior with their daily routines, no matter how small. Perhaps, they had been meeting at their churches, their local coffee shops with their friends, taking daily walks with their dog in their neighborhood park, going to regular events such as birthdays, anniversaries, holidays. Their rituals have provided meaningful connections for them for decades. But suddenly, those rituals and routines are gone, and they must somehow find a replacement, even in an assisted living community or nursing home. Or in your own home without being able to access what you used to do.

But here’s the most tragic part: It seems no one is interested in your story these days, in our rushed, distracted society. It seems there is never the right time to share your story because there is a lack of rituals and routines that can provide the structure to have long and rich conversations. Seniors often lose these opportunities just to tell their stories, to have the time and undivided attention without being hurried or interrupted. You can have lots of people around and plenty to do but still feel isolated, just because our lives feel meaningless.

Val: Besides asking good questions, what are other ways you spark conversations?

Diane: I think the mere fact that I am interested in someone’s story provides the most potent spark.

For instance, I had a blast with a Passamaquoddy Indian man named Wayne Newell, whom I interviewed in Princeton, Maine, where he lives with his wife Sandy on the Indian Township reservation. (Wayne prefers to call himself Passamaquoddy Indian rather than native American.) Wayne, age seventy-seven, is blind and dependent on oxygen from a tank. When I visited him, he was recovering from pneumonia, but said he was so looking forward to our conversation he didn’t want to cancel. He was worried about his voice not being a strong as usual, but we ended up talking for about two hours. I was captivated by his stories of growing up on the reservation, the many challenges he has faced, and how he was able to get a Master’s degree from Harvard.

People are often eager to share not only what they have accomplished, but also what they are still accomplishing. For example, Ernie DeRaps, who’s in his 90s, was once a lighthouse keeper. When he retired at age eighty, he began painting lighthouses. He showed me his collection down in his basement. It was an honor to spend time viewing his paintings. Every single painting of each lighthouse had its own story.

Ernie DeRaps

Val: I notice with your podcast, Conversations about Aging, you typically describe in great detail the landscape of where your interviewee lives. I find that interesting--as if the place where the person lives is part of what defines the individual’s character.

Diane: Yes, I always describe the landscape of where we are in the podcasts. Wayne, for example, spoke about the lake by his home. Listeners of his podcast can learn of his sense of identity through this lake, his connection to this particular place, his sense of history and belonging through the world of this lake. Or through stories of his life on a reservation.

Val: It seems the detailed and colorful descriptions of where your interviewees live help to segue so beautifully into their life stories.

Diane: And here in Maine, in rural settings, it is essential to let your interviewee know that you are noticing these things about their home, about their town, about the woods or the lake or the area. It not only helps them feel comfortable with you, it is a sign of respect and honor.

Val: Do your interviewees like to have their story shared as a podcast and published?

Diane: Not necessarily—some do, and some don’t. Sometimes they don’t respond at all to their podcast once it is up on my website. Some of my interviewees are satisfied just with our conversation itself. One of my interviewees, Leona Chasse, told me, ‘I enjoyed this so much—just the conversation.’

Val: But what a tremendous gift you are giving them, Diane. They are so fortunate to have you there with them.

Diane: This work gives my life meaning. I love synthesizing all the disparate information from my visits to their homes and from their memories. Gathering all the information from our interactions, stories, photos, and natural landscapes—somehow, I try to capture the essence of that person.

Val: And you do that, brilliantly. Thank you for sharing your wisdom with Health Story Collaborative today. We are all storytellers here and you have helped us appreciate even more the power of harnessing our stories.

Diane: I’ve enjoyed it. Thank you.

To learn more about Diane Atwood and her work, please visit www.dianeatwood.com

Val Walker, MS, is a contributing blogger for Psychology Today and the author of The Art of Comforting (Penguin/Random House, 2010) which won the Nautilus Book Award. Formerly a rehabilitation counselor for 20 years, she speaks, teaches, and writes on how to offer comfort in times of loss, illness, and major life transitions. Her new book, 400 Friends and No One to Call: Breaking Through Isolation and Building Community, was released in March, 2020, with Central Recovery Press. Learn more at www.valwalkerauthor.com