Before it all began, we were just regular people, living our quiet life and growing into a marriage. I often shake my head in disbelief that something as dramatic as a brain tumor happened to such a boring couple. You see, we met in a hotbed of nerd-dom, MIT, in a graduate program for organic chemistry. I had come from a small college and felt behind academically, and most of my peers had come with serious relationships while I knew nobody. As I struggled to find my way, I noticed Chris. He exuded calm and kindness in a competitive, charged environment. After a helpful prod from a mutual friend, I summoned the nerve to ask Chris out for a visit to the Harvard Museum of Natural History on our day off from lab. He accepted and asked me to lunch the day before our date. He surprised me by being funny and talkative, and we hit it off. Our time at the museum was almost magical. As it was about to close, Chris and I entered the Earth and Planetary Science room full of minerals and rocks. It was dark outside and the display cases of gems seemed to shine brightly in contrast, and I was also shining with happiness. We extended our time together with dinner, then again with coffee. I felt lucky.

We bonded quickly over our shared interests in organic chemistry, teaching, and family. Unlike most of our peers, Chris had a rich life outside of school, full of family and friends. Rapidly our separate worlds became entwined. We were a team: best friends, partners, each the biggest supporter of the other. He did not ask me to marry him, we decided together. He did not surprise me with a ring, we chose one together. We turned to each other to debrief about work, to discuss our worries, to make plans. We didn’t need much outside of our private world.

In 2007, we were three years into our marriage and everything was just taking off. I landed my first “real” job, we bought our house, we had our first child, and we turned 30. On the last day of 2007, everything turned upside down never to quite right itself again. We were in the Midwest visiting my family, headed to a New Year’s Eve gathering. Chris, luckily not driving, began acting strangely. It was the shock of my life to see my husband unresponsive and in uncontrolled motion, experiencing what I would later learn was a grand mal seizure. I fished Chris’s cell phone out of his pocket and called 911 in a panic. At the hospital, Chris was given anti-seizure medications and sent straight off for a CT scan. Soon after, a clearly experienced doctor broke the news - the seizure was caused by a mass in Chris’s brain. In my shock, the only thing I could ask was, “is it big?” The answer was not encouraging; it was “fairly good-sized.”

Time seemed to unfurl differently after that. Moments blended together in a haze of shock. We flew back to Boston, Chris slept on the plane with our son napping across our laps. My mind was buzzing with white noise, there was only one thought that stood out with clarity – what is going to happen? There would be no quick answer to that…

January was a dark, confusing time as we chased all over the Boston area in search of the right medical team. Finally, we landed at MGH. Chris had an aggressive, awake craniotomy on one of the longest days of my life. The rest of the year was a dark blur of a difficult recovery from the surgery, daily radiation treatments, cognitive rehab appointments and a terrifying uncertainty. We also had a perplexing diagnosis for Chris – low grade glioma. The doctors were absolutely clear: there is no cure, the tumor would come back and be more aggressive, but the prognosis was that Chris would likely live for 10-20 years.

At first the disease surveillance scans were frequent. Gradually the time between them lengthened as they came back stable. As partners, our shock turned to coping with a long-term disease. We took things one day at a time, waking up, readying our son for daycare, working. When one of us had a particularly bad day, we learned to get through it by staying in motion. Vigorous house-cleaning, raking the yard, cooking on the grill – these things provided helpful distractions. Through it all we had each other. We talked about everything as we always had, but we became even closer. Slowly, our life did return to something resembling normal, but the undercurrent of wondering when the tumor would return was always there. After a couple of years, the tumor began to feel surreal and we discussed this endlessly. How could life feel this normal? Did anyone else understand that we were waiting for the other shoe to drop? There were no days that Chris did not think about dying and no days without the incurable tumor crossing my mind, but there was still work to do, our son to raise, dinner to fix, and bills to pay.

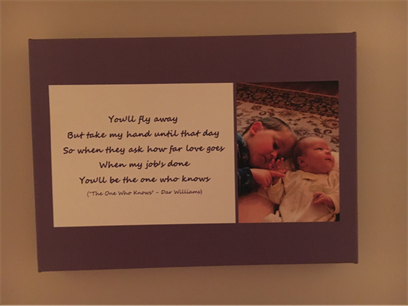

This long-term, terminal diagnosis threw a wrench in our family plans. If we hadn’t already had a child, perhaps we would not have chosen to bring children into the situation to avoid the future pain of loss. But, our son was already on this path with us and we had always wanted to have more than one child. We interrogated the doctors about genetics and felt assured that the kids’ risk would not be higher. We “just” had to reconcile the idea of a new baby with a terminal brain tumor… Over time, “no” gradually turned to “yes” for Chris, and neither of us looked back. Our second pregnancy brought a sweet joy. The brain tumor gave us a deep appreciation for this chance at new life. Our son was thrilled when he learned he would be a big brother! One day in the middle of a science seminar, I looked down and smiled at my black and white patterned shirt wiggling in time to the first palpable baby kicks. The day we found out the baby was a little girl, Chris and I were both overjoyed and marveled at our great luck to parent a girl along with our boy. Just before she made her entrance to the world, Chris and I slowly walked the hallways of the hospital, pausing frequently for contractions, Chris supporting me as he always did. Despite the pain, I remember thinking how improbable this moment was in light of his illness, and trying to etch it in my memory. As she was born, Chris played his favorite song The One Who Knows and we both shed happy tears. We delighted in this little girl, knowing that nothing about life was guaranteed and still, here she was somehow.

As our family expanded to four, the richness of life also expanded. Chris reveled in being a dad – he was funny, always able to diffuse difficult moments with a joke. He was kind, quick to enfold his children in hugs. Chris grew professionally, becoming a leader at work. For several years life was a beautiful, normal dance of “do you need to leave early this morning, I’ll pick the kids up tonight, can you grab some milk on the way home, do we have plans this weekend, let’s go out for pizza.”

That is, until the tumor came back. It’s interesting, when I anticipated the recurrence, I always thought it would be instantly devastating. Instead, we found that recurrence was gradual but progressive. It happened like this: Chris experienced a slight uptick in focal seizures in the months leading up to his annual MRI. Instead of the usual “looks good” post-appointment text, I received one that just read “appointment over.” Chris reported that there was an area of concern that could be tumor growth. A biopsy revealed Grade 3 tumor, more aggressive than before, but still, Chris was himself. We were lucky in that respect. He entered a clinical trial and chased all over Boston for special MRI scans and long hospital days, all the while keeping fastidious track of cycle days, medications, and symptoms. We were worried, but we were doing something about the tumor.

Things went smoothly, until the awful day Chris's clinical trial doctor popped her head in the exam room to exclaim that his tumor had shrunk by 30%, but soon came back to say no, sorry, there was a mistake in the software measurements. The tumor had actually grown so much Chris was ineligible for the clinical trial.

After four months of normal time on Temodar treatment and a stable MRI, Chris had a grand mal seizure once again. The dread of the next MRI scan was sickening, and it brought worse news than we imagined – not only was the tumor growing but it was also infiltrating a second area. Another biopsy revealed that the tumor had progressed to glioblastoma. But still, Chris was himself, working on his laptop not 48 hours past brain surgery.

But then, Chris declined suddenly. He began having lengthy focal seizures, his vision deteriorated, and reading was problematic. He went on emergency radiation treatments and last resort Avastin infusions. After a whirlwind of daily hospital trips, we had to wait and watch how the tumor responded.

We were on borrowed time. We did unpleasant things: estate planning, transitioning all of the bills to me. Chris showed me where the water shutoff to the house was and where to find manuals for the lawnmower and snowblower. Those discussions about how to carry on without him were excruciating. Chris’s main concern was that the family would be taken care of, and in light of the painful fact that he would soon die, he did everything he could to ensure it. Most importantly, we tried to be present for each other and the kids. We noted how difficult it was to “live in the moment” for an extended period of time, but we tried. We enjoyed simple moments, knowing that there would not be many left: walks together, date lunches, family outings, time at the park, beach trips. Chris did not feel the urge to check off an ambitious bucket list, but rather he treasured the kind of togetherness that can be so easily taken for granted.

All the while, we braced for the worst. For a few months, it didn’t come and we started to muse over the fact that it had not happened. Summer turned to fall before the tumor grew, but still Chris did relatively well even after we received this news. Our hearts were full and breaking as we fit in lots of lasts – last Halloween, Chris’s 41st birthday, trip to the Midwest to see family, Thanksgiving. As the holidays approached we knew that if Chris made it to them, they would be the last as a family of four.

As we were preparing to leave the house to pick out a Christmas tree, Chris had a grand mal seizure. Just as he came out of it, another started. I did my best to stay calm and administer medication, but then a third seizure started. He was taken by ambulance to the ER and almost died from respiratory depression. Somehow, Chris made it through. We were lucky. We had not been ready to say goodbye despite all of our preparation.

Chris came home by ambulance on hospice services. It was a terribly difficult December as his right side weakened, seizure activity increased, the number of medications was overwhelming, and the end was drawing close. We set small goals, trying to make it through Christmas and have a nice family time. Somehow we did, but afterwards Chris was less peaceful and I could no longer care for him well. In our past discussions about this end stage we had always prioritized Chris being at home but realized things could get out of hand and a hospice facility might be needed. Chris had wanted to shield his children from the worst of his decline. The moment arrived when he felt he should not be at home and I agreed.

On yet another difficult New Year’s Eve, we got word mid-morning that a bed opened at a hospice house, and Chris left our home by ambulance, just a couple of hours later. To say it was hard to watch him leave doesn’t begin to touch the emptiness of that moment. As he was loaded into the ambulance, Chris lay on a gurney facing the front of the house we bought together and raised our family in. I often wonder what was going through his mind. Was he desperately sad? The kids and I had to watch him leave, knowing he would never return to us, and we cried together for a few minutes after he left. My solitary journey to the hospice house was marked by shock that this was actually happening. Despite my wanting time to stop, Chris faded over the next eight days. He was mostly peaceful, always loving, and truly serene in the end. When he could no longer speak, he telegraphed his love by winking his good eye slowly several times. Chris died on January 8th.

Chris’s brain tumor changed the course of his life and ended it early. It shaped mine, too, and that of our children, in ways that we are only just discovering. Telling this journey is something that helps me process everything. But, Chris was so much more than this terrible cancer. Before the tumor was discovered Chris already embodied gentleness, loved a good laugh, was whip smart, always kind, and steadfast in his love for family and friends. These things did not change in the face of terminal illness. If anything, Chris doubled down on the way he lived knowing his life would not be a long one.

Now, Chris is gone and I’m no longer dreading his death but I’m desperately missing and loving him in his absence. I am left with a hundred thousand memories to carry as my life continues without my partner. I move forward reluctantly but still, I move forward. I am learning about myself and my capability as an individual. When things seem hard, I remember Chris’s unwavering opinion that I could do it, whatever “it” was, and I remember how he managed so admirably under his impossible circumstances. On my better days I focus on the feeling of being lucky. I was lucky to know Chris, to learn from him, to love and be loved by him, and to share a life with him. I told Chris before and I will say it again now, in a heartbeat I would do everything all over again with him.

Listen to Chris and Betsy here, in an Audio Story recorded in August, 2018, six months before Chris died.