By Kelly Keena

I wouldn’t say I was reckless, instead I would call it young and lacking confidence. I was a college student, living with two friends in a fabulous neighborhood in east Denver, waiting tables, and living a very active, ahem, nightlife. Never any of the big drugs, mostly drinks. A lot of drinks. And cigarettes, dammit.

When I did not feel good on my twenty-first birthday, I pushed through. Stubbornness has nearly killed me and saved me. I went out anyway to the bar owned by the future Governor and played pool with my friends and did shots of whatever they handed me. The next day, I felt more than hungover. A week later, I was in a drug-induced coma with a stubborn staph infection in my lungs. My last rights were read, my friends told to say their goodbyes. And then, I woke up and recovered for the next seven weeks in the hospital. This was the beginning of a very long slog through a chronic disease.

Two years later I had the diagnosis of bronchiectasis due to the infection that ripped through the lower left and upper right lobes of my lungs. Two places that live inside my body that are unable to do their jobs. As a grad student doing my internship teaching environmental education, I taught form and function as related to the beauty of the natural world. The form of my lungs overtaken by an infinitely small bacteria and they could no longer function.

My friend’s mom offered me a job at her small coffee shop right off of the main artery to the Rocky Mountains, at the highway exit where I argue you get the most spectacular welcoming view of the first range of snow-covered peaks. We had some tourists, but our customers were mostly locals from the mansions and less-than-mansions scattered throughout the trees. One of these regulars was a nurse in the cystic fibrosis (CF) unit at our Children’s Hospital

For months we shared a similar exchange. She would hear me cough and say, “That sounds like a CF cough.” And I would reply something like, “It’s not CF. It’s bronchiectasis from my staph infection.” I called it “my” infection because somehow I had proclaimed it as part of my identity. She would then reply, “You should ask your doctor.” I would hand her the coffee and thank her.

Finally, I did ask my doctor. We would have a similar exchange as the nurse and I, only this time I was on the other side of the argument. He eventually caved and ordered a sweat chloride test. There is a higher concentration of salt in the sweat of people with CF and this is used as a diagnostic tool. To measure the salt content, they put a solution on a small cotton pad on the inside of my forearm. They connected electrodes that created tiny buzzing pulses causing the area to sweat, which was absorbed by the cotton pad. It didn’t hurt, the sensation was more like an annoying scratch. The nurse attached the electrodes and casually said, “CF, huh. You should have been dead a long time ago.” I guess I didn’t know what CF was.

Two weeks later, I was studying for an exam with a friend sitting at her oak brown kitchen table worn by the coloring of her young daughter. My doctor called and I listened to him say that the test was inconclusive. I stared at the framed photo of my friend’s mom in a funky dress, pregnant with my friend and holding a cigarette in one hand, a martini in the other. Our medical understandings have evolved so much in our short lifetimes.

I went back for more tests. They drew blood and sent it for genetic sequencing. In total, the process took about two years. Two weeks before my wedding to the man who does not wince when I cough, in my parents’ backyard with the same beautiful Rocky Mountain backdrop, I received a call from National Jewish respiratory hospital. I had cystic fibrosis. I needed to come in and connect with the adult CF clinic. That same summer, a 63-year-old man was also diagnosed with CF.

On the heels of the diagnosis, I had pneumonia again, one week before the wedding. I had pneumonia three to four times a year since the staph infection. Stress had a way of laying me out. On good days, my cough sounded like a gurgle of sludge. With pneumonia, the gurgling was muffled, my lungs full of putty-like mucus, drowning in my own body. Planning big events is difficult as pneumonia was difficult to pencil into the calendar.

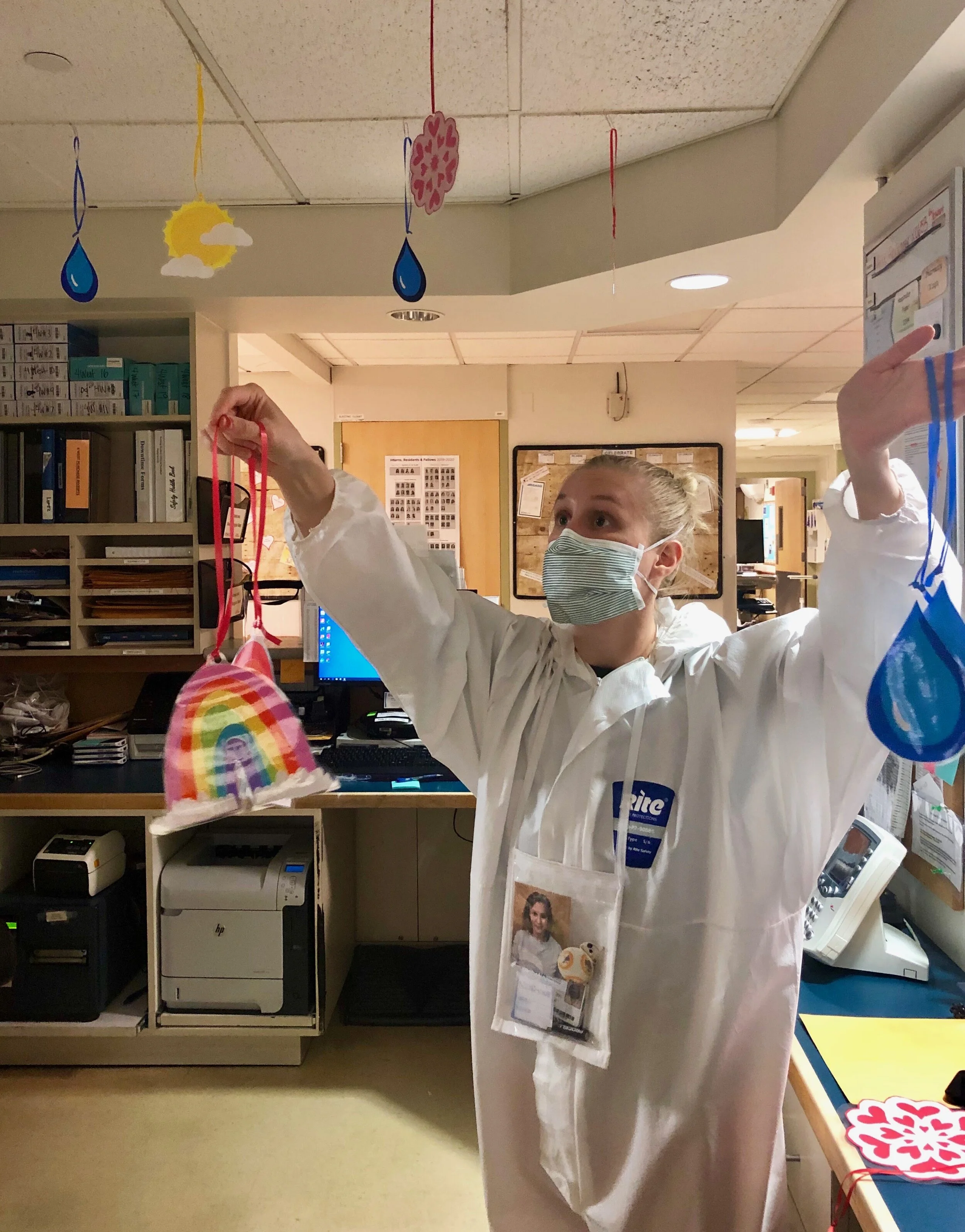

This hospital visit was new. Different. I had a private room without the flimsy curtain that was intended to separate patients but didn’t. Everyone from the medical teams and custodians and those delivering trays of rubbery food was gowned, masked, and gloved. I felt like an alien under investigation. Only later did I learn that the protective measures akin to what we are all so used to seeing throughout Covid, were to keep from spreading a special bacterium common in CF patients. I was not yet skilled in the art of asking questions and advocating for myself. I just sort of went with it.

My doctor and nurse had wry humor and wit and a reasonable dose of seriousness. They listened to me, to my lungs and to my words. They continue to lead my care team more than twenty years later. With CF now added to my identity, I got an IV between my toes. The veins in my arms protested any attempt to intrude. I was grateful for their resistance. I had a sleeveless wedding dress and avoided the dark purple and yellow smears that lasted for weeks after the needles.

I never got to tell that nurse that she diagnosed me. Without her, I wonder if anyone would have figured out that I had this genetic recessive disease if she didn’t like coffee. Nettie, if you’re out there, thank you.

I call CF my 2x4 to the head, my awakening into self-care. I still feel a bit of shame when they refer to me as a former smoker at the clinic. I automatically reply, “I was young.” My husband who doesn’t wince when I cough calls it my “sit-your-ass-down” disease. In my late teens and early twenties, I was not taking care of myself. I didn’t know who I was aside from wanting to teach children how fragile and resilient our natural world is. I learned that I am also fragile and resilient. CF is now my barometer and friend that tells me when it’s time to rest, take good care, and sit my ass down.

The acceptance was not readily available, though. I am only talking about having CF now, after all this time, to you and even to my family. It has been an intensely private experience. Like my hardened off veins, I shuttered my life with a chronic disease from everyone. I commonly hear, “but you don’t look sick.” Even my husband and daughter are just now learning about the intricacies of CF inside of my mind, although they are most attuned to my lived experience. I will always wonder why it is so much easier to write for strangers than to admit such things to the two people who are my world.

CF for me is not as much about the illness as it is about the recovery. Chronic healing is a life of getting laid out and then getting up again. And again. And again. Resilience can be a tricky term, sometimes used to shame those of us who can’t get up again. I argue that there is nothing wrong or bad about laying down for a while. Recently, I laid down for five years crippled by depression and anxiety from repetitive hospitalizations. I think there is a misunderstanding of chronic disease, that it is always the physical illness. It’s not. It’s actually always the looming threat of illness while working to maintain the demands of life. And being easy on ourselves for the complex mental gymnastics that accompanies normalcy and illness. Chronic disease is as chronic for the body as it is for the mind.

Chronic illness has become my greatest teacher. It reveals the grand paradoxes of my one life – the beauty of small things like a bird call and the pain of large things like cancelling an international trip with my daughter the morning of departure because my lungs were bleeding. Chronic healing has meant a life of appreciation, acceptance, and yes, sometimes terrible physical pain and mental exhaustion. Chronic healing is what we do in chronic disease. We don’t have a choice. It takes us to the edge and then allows us to recover. What I do in that recovery, I hope, defines me more than when I lay down and surrender to a rest.

Kelly Keena, PhD is an environmental educator and adult living with cystic fibrosis near Denver, Colorado.